Strict Examination Criteria Needed For Drug Patents

Background

Thus, it is very important to set the rigorous patentability standards for granting a patent on a particular drug otherwise its repercussion will not only be detrimental to the general public (esp. patients) but also to the entire patent arena in the form of an extended absolute monopolization period, exploitation of other competitors, and more importantly as an impediment the production of generic drug and causes a delay of the entrance of generic drugs in the market.

The irony of Malaysia’s patented drugs

A pharmaceutical company famous for its HIV/AIDS drug which combines Lopinavir and Ritonavir did not file for patents on the two base compounds in Malaysia. However, from 1999 to 2006, several secondary patents were granted on the base compounds by the Malaysian intellectual property office. All over the world, the base compounds for patents for Lopinavir and Ritonavir have expired between 2014 and 2017 but in Malaysia, the last secondary patent will expire in 2027. It shows that even after the expiration of base compounds in Malaysia and other counties, the patent life of the drug has increased by 10-12 years. As a result, the availability of a generic version of such drugs remains a far cry in Malaysia. One unavoidable issue that arises due to such a scenario is the high prices of HIV/AIDS drugs as per the Malaysian Competition Commission review of the pharmaceutical sector.

While citing the data of the Malaysian health ministry, it was shown that the patented drug cost US$1,489 (RM6,112) per patient per year under a Health Ministry procurement contract, whereas a generic version of such drug can be obtained at US$268 (RM1,100) from India.

Like other IP countries, Malaysia also needs to ensure that the drug patent application has an invention that is new, involves an inventive step, and is capable of industrial application. But such criteria or standard is not defined in a country, the ultimate repercussions would be negative such as extended monopoly period which would further create an impediment for a generic version of drugs from entering the market.

The above argument brings our attention to the commonly used strategy of pharmaceutical companies called ‘patent evergreening’. It is referred to as the practice whereby pharmaceutical firms extend the patent life of a drug by obtaining additional 20-year patents for minor reformulations or other iterations of the drug, without necessarily increasing the therapeutic efficacy and thus gets multiple secondary over a pharmaceutical compound.

Therefore, it is essential for the ministry for IP and the patent office to come up with more stringent patentability criteria for pharmaceutical patent applications in order to avoid the practice of secondary patents and patent evergreening.

Notably, the data from the US Food and Drug Administration show a decline in the number of chemical entities for medicines since 1994 but at the same time, it reveals that there is an increase in the number of registrations of patents. This growth in pharmaceutical patents is a problem not only in the developed countries but also in the developing countries said Ms. Sangeeta, legal advisor Third World Network. In furtherance of the same, an Inquiry by the European Commission in 2009 unveiled that in relation to 219 drugs, out of the 40,000 patent applications granted and pending, 87% were secondary patents, Ms. S. Sangeeta added. She further said that the delay in the entry of generic versions caused a loss of around 3 billion euros.

While extolling the patentability criteria of Pharmaceutical drugs in India and Argentina, she added that weak patentability criteria for pharmaceutical patent applications lead to inaccessibility of life-saving drugs to needy patients because of its unaffordable prices.

Considering “patents evergreening” cases and other detrimental strategies of Pharmaceutical companies in 2016, it was recommended by the Report of the United Nation Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines that WTO Members should adopt and apply rigorous definitions of invention and patentability that are in the best interests of the public health of the country and its inhabitants to curtail the evergreening of patents, and to award patents only when genuine innovation has occurred. Condemning the court process as time-consuming and expensive, Ms. S. Sangeeta proposed guiding measures for Malaysia stating that it should introduce an administrative pre- and post-grant opposition system to patents. Such a mechanism would ensure a more rigorous examination of patent applications and thereby generates better examination practices. Moreover, it would allow an interested party (generic companies or patient groups, etc.) to oppose the application before the patent is granted, and similarly post opposition allows any party to oppose a patent application after the grant of patent. This is how it will be helpful for the patients diagnosed with cancer, Hepatitis C, and rare diseases whose treatment is a far cry for such people because of their high pricing.

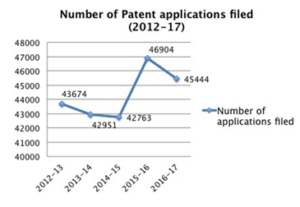

With respect to the India patent scenario, the following shows the patent trends between 2012-2017: Here

Conclusion

The grant of patent connotes monopoly over the patented subject matter and if it is granted so easily without applying firm standards and tests, it would not harmonize the purpose of IP law. The objective of IP law is to provide incentives to create and serve the interests of the public by promoting economic growth. Interestingly, in the pharmaceutical sector, the rigorous application of patentability standards becomes more important because the production of medicines depends upon them. Thus, their direct nexus with the public health which constitutes a part of public interest cannot be overlooked. So if the evergreening strategies which ultimately extend the monopoly time, are not curbed, the result will be unaffordable high prices of the medicines and delay in the entrance of generic drugs in the market. High pricing of the medicine is accessible to only a limited number of people who are rich but the large segment of the people who cannot afford such high pricing medicines have to suffer by relying on their fate. Thus, the role of patentability standards is very significant in the pharmaceutical sectors.

Related Article: central drugs standard control organisation

Author: Lokesh Vyas, Intern at IP and Legal Filings, and can be reached at support@ipandlegalfilings.com.