Quasi-Easement

Introduction

The doctrine of easement is the enjoyment of certain rights over the non-possessory title, that is, having certain rights over the property which is not owned or possessed by an individual. The law by this doctrine permits an individual to use another person’s property for specific reasons. Though an individual gets some right over another person’s property, these rights are limited and the title of the property remains with the original owner only. The Indian Easements Act, 1882[1] deals and governs the laws related to easements in India. Section 4[2] defines the easement as the right of the owner of the land to do or to prevent doing something upon the land which is not his own for the beneficial enjoyment of his own land. For example, going through the neighbor’s land for fetching water from the well for the enjoyment of his own land, when that is the only way to reach the well. In this case, a person will be said to have an easement right over the land of the neighbor but only for the purpose of fetching water. In Metropolitan Railway v. Fowler, the definition of the easement was stated by Lord Esher as “some right which a person has over land which is not his own”[3]. The land for the beneficial purpose of which the right is exercised over other land is called dominant heritage whereas the land on which burden is trusted is called servient heritage. The owner of the dominant heritage is called the dominant owner while in case of servient heritage, he is the servient owner[4].

History

The idea of easement dates back to the time when people started living together in society. Recognizing the private properties of individuals in those societies gave rise to the right of easement. The right was given birth for the mutual benefits of the individuals in a society with a pinch of morality, allowing the third parties to enjoy certain benefits on the land which are not owned or possessed by them. The term easement was derived from the word ‘aisementum’ which means comfort or privilege and thus, giving the privilege to use something which is not yours.

Quasi-easement – Meaning

The concept of quasi-easement is related to how the land is used in the past, that is, before being transferred or bequeath. This type of right is implied from the prior or existing use of the land. It arises when earlier an entire land is owned by a particular person and he used one part of that land for the benefit of the other. If he, later on, transfers the benefitted land, then the easement for the use of the servient land will be implied in favor of the transferee. These are called quasi because the easement in such cases is not absolutely necessary but after being separated from the main property, is necessary for the reasonable enjoyment of the property. Clauses (b), (d), and (f) of Section 13[5] of the Act deals with quasi-easement as per which if an easement is continuous, apparent, and necessary for the enjoyment of property as it was before the transfer or bequest, then the transferee or lessee and also the transferor and legal representative of the testator be impliedly entitled to such easement unless the opposite is expressed. Such type of easement can be given by expressed or necessarily implied intention.

For the easement to be called as ‘quasi-easement’, the existence of the condition ‘continuous and apparent’ is must without which the easement would not come under the category of the same. Continuous easements are the one whose enjoyment continues without a human act while the apparent are the ones the existence of which is shown by some permanent sign which upon careful inspection would be visible to him[6].

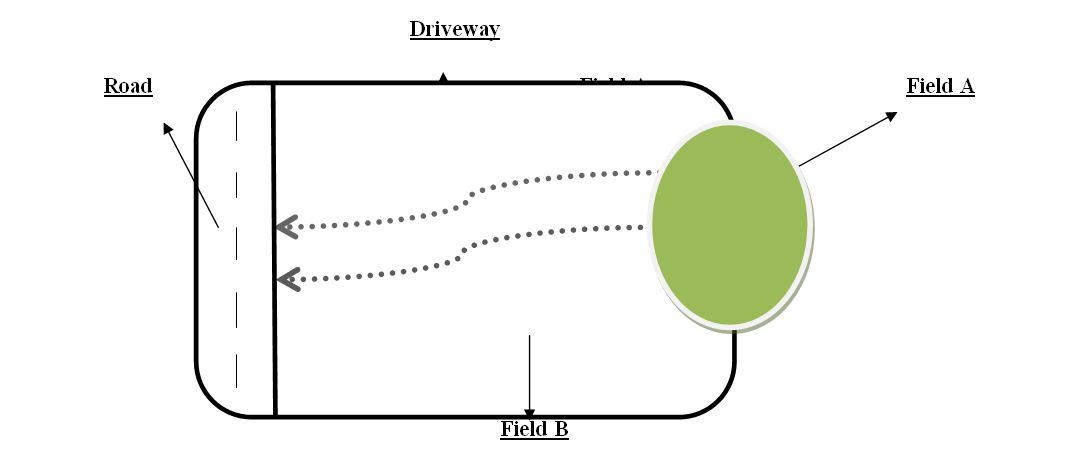

For example, in the following image, the whole land is owned by Mr. X, and during the ownership; he uses the driveway to get to the road from his Field A, that is, he uses one part of his land to get the benefit of the other land, which in short is an easement. If now, later on, Mr. X sells Field A to Mr. Y, thereby retaining the other part with himself, then with the transfer of Field A, there will be implied right of the easement to Mr. Y, unless the opposite is expressed, over the driveway just like the way Mr. X used to engage in before the transfer of the land. Mr. Y for the beneficial enjoyment of his land, that is, Field A has a right of way over the land of Mr. X. This is called quasi-easement since the use of the land is ‘continuous and apparent’.

In the case of Brij Mohan Lal v. Hazari Lal & Ors.[7], before the partition, parties were co-sharers of certain properties. There was a drain which carried off drain water from the property. Thus, the use was continuous and apparent. It was held that the parties claiming the drain as a quasi-easmentary right will be entitled to the use of the drain since they were enjoying it before the partition.

Wheeldon v. Burrows[8] is one of the landmark cases related to quasi-easement. As per the facts of the case, Wheeldon owned land and a workshop both adjacent to each other and both of which he put on sale. The land was sold to C while a month later; the workshop was sold to D. C built boardings on the land which blocked the light to the windows of the workshop. D in consequence knocked down the boardings, the result of which was C suing D for trespass. D appealed in defense that he had an implied right of easement over C’s land for access to light. The issue here was whether D had a right over the land for the light to enter through a window or not.

The court while deciding the case in the favor of C stated that only those continuous and apparent easements are implied in the cases of grant which are necessary for the reasonable enjoyment of the property conveyed and have been benefitted by the part granted during the period of unification of ownership. In the present case, Wheeldon had not reserved the right to access the light while he conveyed the land and thus, no such right was passed by him. It was found that neither anything was indicated in the conveyance nor any implied rights that were granted prior to or on the sale of the land existed. The following three essential conditions for the implied right of quasi-easement was established:

- Prior to the transfer, the land must be owned by a single person and that must have been quasi-easement in favor of the transferred part over the remaining part.

- The quasi-easement must be apparent and continuous prior to the transfer.

- It must be necessary for the reasonable enjoyment of the transferred part.

Thus, these three above-mentioned conditions are necessary for an easement to be called quasi-easement. Quasi-easement is an easement practice that a particular person engaged in prior to transfer when he used to occupy the whole land.

Difference between Easement of Necessity and Quasi-Easement

Though both these types of easements, that is, easement of necessity and quasi-easement are dealt with in the same Section which is Section 13[9] of the Act, they are different from each other and are applied in different situations. Clauses (a), (c) and (e) of the same Section are related to the easement of necessity while the other three are of quasi-easement.

The former deals with the situation where there is absolute necessity while the latter deals with the situation where the necessity is qualified. For quasi-easement, the condition of ‘continuous and apparent’ use must be satisfied first while in the easement of necessity applies without any condition. The former cannot be precluded during the transfer, that is, there is no need to mention it expressly, it is an implied easement. While the quasi-easement, may be expressed or may be implied.

In Sukhdei v. Kedarnath[10] and also in Karunakaran v. Janaki Amma[11], it was held that for an easement to be easement of necessity, the land over which easement is claimed has to be the only option. If there’s any other way, even if it is inconvenient, an easement cannot be claimed on the ground of easement of necessity.

Conclusion

Thus, it can be concluded from above that the right of easement is right over someone else’s property with respect to certain specific things for the beneficial enjoyment of one’s own property. When this easement is of continuous and apparent nature and is necessary for the reasonable enjoyment of the property, this easement gets converted to quasi-easement. Quasi-easement is an implied right and may not be mentioned expressly in the lease deed or any other agreement. However, the condition here is that the property must have been owned by the same person before the transfer of that property took place. It is the right wherein though the owner of the property gives others some rights over his property but still at the same time, he only keeps with himself the title of the property, being the lawful owner of that property.

Author: Khushi Agarwal, in case of any queries please contact/write back to us at support@ipandlegalfilings.com or IP & Legal Filing.

[7] Brij Mohan Lal v. Hazari Lal & Ors. AIR 1936 All 90.

[8] Wheeldon v Burrows (1879) LR 12 Ch D 31.

[9] The Indian Easements Act, 1882, § 13.

[10] Sukhdei v. Kedarnath, 40 Punj LR 787.

[11] Karunakaran v. Janaki Amma, 1988 (2) CCC 137.

[1] Indian Easements Act, 1882, Act no. 5 of 1882.

[2] The Indian Easements Act, 1882, § 4.

[3] Metropolitan Railway v. Fowler, 1 Q.B. 165, (EWCA: 1892).

[4] The Indian Easements Act, 1882, § 4.

[5] The Indian Easements Act, 1882, § 13.

[6] The Indian Easements Act, 1882, § 5.