Can Braille Be Registered As a Trademark?

Introduction

Trademarks are no longer confined to words, numbers, or devices. Admittedly, anything which could be used to distinguish one’s merchandise is being put out for statutory protection. This is primarily because of the clash between the traditional concept of trademarks and the ever-growing need to find newer ways to differentiate one’s product and services from competitors.[1] Thus, the nature of trademarks has also morphed into unconventionality, where protection is often sought for smells, stand-alone colours, sounds, and even buildings.[2] This new set of marks is often referred to as non-traditional trademarks, and the qualification for their registration, as opposed to a traditional mark, is substantially higher.[3] But the extent to which a particular thing might be trademarked is a question of relevance for two important reasons: First, some objects, by virtue of their very nature (or the societal significance attached to them), cannot be trademarked—for example, the tricolour or the national emblem.[4] Second, the qualification for registering a trademark, both traditional and non-traditional, essentially remains the same. Thus, in the present scheme of things, where unconventionality is tested against the conventionality of predominantly outdated statutes, I intend to answer if braille can be registered as a trademark. I do this by demonstrating the statutory criteria for trademark registration and then applying the set criteria to check the registrability of braille.

THE THREE STAGES OF INQUIRY

A trademark is a mark capable of being graphically represented and it can distinguish the goods and services of one person from another person.[5] So, the three qualifications of a trademark are: it is a mark, it is graphically represented, and it has the ability to distinguish itself.[6] Thus, if braille fulfils these three qualifications, it, too, could be registered as a trademark.[7]

Is Braille a ‘Mark’ ?

The definition of ‘mark’ in The Trademarks Act, 1999 (‘Act’) merely prescribes a set of signs or symbols capable of ‘conveying information’ about the products and services in question. The idea is that the proprietor needs a sign which can be used to communicate to its potential customers and distinguish their goods. The definition for mark is inclusive, meaning thereby, it not only indicates the things already mentioned but also widens the import of the word mark to include things which are not mentioned therein[8] and can include anything in the imagination of the proprietor to use as a trademark.[9] This is corroborated by the approach adopted by the European Union (EU), where under the European Union Trade Mark Regulations (EUTMR), they have expanded the scope of marks to include sound, multimedia, holograms, and a residual ‘other’ category.[10] Worthwhile to note here is that the Court of Justice has held that the concept of a sign is not limited to visually perceptible matters. As a result, both sound and smell have been held to fall within the notion of a sign.[11] In fact, if the subject matter could be perceived by one of the five senses, it could be considered a sign.[12] It has been held that this term is very wide in scope and should be taken to mean ‘anything which can convey information’.[13] However, this would not mean that any suppositive sign or symbol can be presented for registration because of two reasons: First, if registration is sought for every sign which purports to mean something, it will cause significant inconvenience not only to the registry but also to stakeholders involved in the process. Ganjee describes it best as ‘discomfort generated by overboard applications’.[14] Second, mere abstract information cannot qualify as a mark, as it has to take a specific format.[15] The reason is that a trademark, by its nature, creates an exclusive statutory right in the holder to use a specific mark and prevents the competitors from using said registration. Thus, a problem arises when the mark is a mere abstraction and does not, in its fullest, describe what ought to be registered (or protected). So, a mark which cannot disclose the same cannot be registered. The very nature of braille resolves this caveat, for it is not a mere abstraction of the mind; but rather, a standard form of representation of characters and numerals for blind people to read.[16] Meaning the mark of a company in braille could only be represented by a certain set of dots embossed on the product in a specific manner.[17] Not to mention, these dots, due to being embossed according to a specific standard and in a specific manner, would only mean what they represent and, therefore, leave no scope for interpretation to mean anything else. In summation, there is no reason, in principle, why braille could not be considered a mark. Moreover, an open approach to this effect is welcomed in the EU trademark regime, as it benefits consumers from different cultural backgrounds and with varying degrees of literacy.[18]

Is Braille Distinctive?

‘Distinctive’ means distinguishing a person’s goods and services from competing goods or services of another.[19] Being able to distinguish one’s trademark falls at the centre of the trademark law, as otherwise, it is liable to be rejected under Section 9(1) of the Act. However, the proviso contained therein states that a trademark shall not be refused registration if it has acquired distinctive character before the date of the application.[20] Thus, a trademark can have two types of distinctive characters: inherent and acquired, where a generic or descriptive (non-distinctive) mark acquires secondary meaning, fulfilling the requirement of the distinctive character. In other words, a mark distinctive or nurtures such decisiveness.[21] It would appear that braille by itself may be distinctive of the product. American Foundation for the Blinds suggests that braille is a system of raised dots that can be read with the fingers by people who are blind or who have low vision. It further adds that braille is not a language. Instead, it is a code by which languages may be written and read.[22] Thus, even if braille is not a traditional set of words or symbols, they assist blind people to understand. For example, when registered in words, ‘SAMSUNG’ will read ‘SAMSUNG’ independent of the language since every language will still indicate the same meaning, irrespective of the script. Admittedly, so will the braille registration. In this sense, a braille mark could be inherently distinctive. Besides, apart from the factor of inherent distinctiveness, it could be recalled that the proviso of Section 9(1) of the Act could still be effective and must be read along with the common law understanding of trademarks in the cases of passing off. The Bombay High Court in Consolidated Food Corporation vs. Brandon & Co.[23] observed that a trader acquires a right of property in a distinctive mark merely by using it upon or in connection with his goods…the trader who adopts such a mark is entitled to protection directly as soon as the article having assumed a vendible character is launched in the market…common law rights are left wholly unaffected.[24] (emphasis supplied).

[Image Sources: Shutterstock]

Additionally, Bansal argues that when adopting or launching a new mark for his product, he is not bothered about any consideration except to ensure that he does not overstep the rights of someone else using a similar mark.[25] Thus, it would seem apparent that registration is not necessary for a braille mark to be used, for if the proprietor can show distinctiveness, he can claim a remedy under the action passing off. Moreover, if a braille mark is capable of showing distinctiveness due to its use, Section 9 is no bar to its registration. Because, in both cases, priority in the adoption and use of a trade mark is superior to priority in registration.[26] However, this comes with a caveat: Although denoting the same thing, braille would not be a traditional mark. For example, the word ‘SAMSUNG’ can be trademarked in any language and it would still fall in the category of traditional marks, as it would be a word, device, or at best, numeral registration. But seeking to register the same in braille would entail embossing raised dots on the package of the product and the product itself. So while the braille would still read ‘SAMSUNG’, the medium of expression, perception, and representation would change entirely. Accordingly, braille is a non-traditional mark, and therefore, the standard of distinctiveness would also be different.

Can Braille Be Graphically Represented?

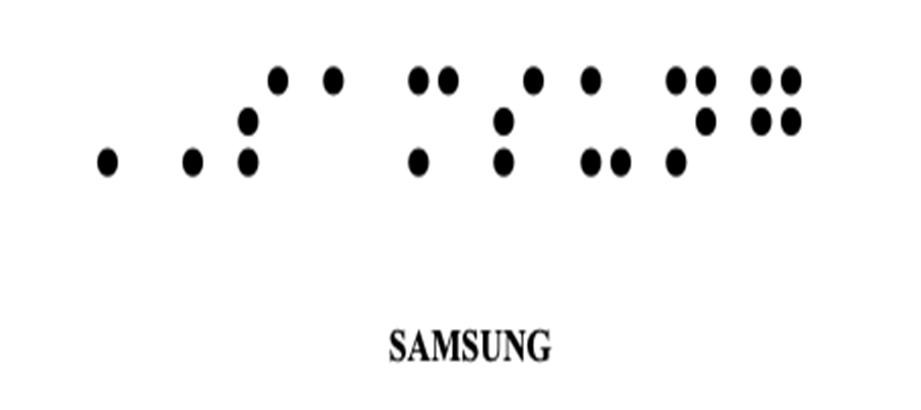

According to the rules, graphical representation means a representation of a trademark that is represented or capable of being represented in paper or digitised form.[27] Essentially, the capability of graphical representation must be realised on the application form[28]—that is, rather than depositing a mark, the proprietor ought to deposit a representation of the mark[29], so everyone can understand what has secured registration.[30] In other words, the test of graphical representation has a three-fold purpose: it ensures that the trademark ought to be registered is not already registered in the journal, informs proprietors not adopt a mark similar to or identical with the one being granted registration[31], and assists the registry in ensuring that a mark which falls within the confines of Section 9 is not registered.[32] Safe to say here is that the test of graphical representation holds crucial importance in registering a trademark. It is, in fact, a sine qua non across all common law jurisdictions. In that view, there is little doubt that braille can be graphically represented. For example, at the time of application, the word ‘SAMSUNG’ in braille could be represented by submitting a picture of embossed dots and by giving deception thereof (See figure below).

Having said that, it must be recalled that a braille mark is a non-traditional mark. Thus, the graphical representation requirement would be slightly different. For example, a caveat for the registration of tactile marks (a type of touch mark) was raised in the case of Neoperl v EUIPO[33] (Neoperl) & in Haptic.[34] In Neoperl, EUIPO rejected an application for a tactile mark since the tactile aspect of the product in question was not apparent from the graphical representation and was merely a description of it.[35] Similarly, in Haptic, the application was rejected because it was impossible to ascertain what the mark was. In both cases, the reasoning used is cogent inasmuch that a description cannot suffice the registration aspect since it can raise doubts about the subject and scope of the graphical representation[36] Admittedly, to apply braille on a product without delineating to other proprietors how the braille would feel on such a product means going beyond the statutory protection of the applied mark. For instance, if braille is applied to a plastic product, there can exist more than one impression of how the braille would ‘feel’ on such plastic. However, this reasoning is not necessarily applicable to a braille mark for two reasons: First, the strict (and almost impossible) test of graphical representation for registration of a touchmark will virtually never be fulfilled. And second, one must take into account that aspect of the relevant public in this context. A braille mark would be directed towards a specific community of people who can differentiate only based on touch; therefore, a strict standard of graphical representation would be unnecessary.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The discussion conducted has rendered two crucial observations. Firstly, a braille mark could be registered because it meets the high statutory thresholds. And secondly, the statutory criteria for registration of traditional and non-traditional marks remain the same, where ingenuity in new trademarks is currently being tested upon the fixed anvils of registration. Thus, the modus operandi here should be to make a cautious retreat from the tests applicable to traditional marks and have a unique approach for registering non-traditional marks.[37] For example, in the United States, one can get a sound mark registered by submitting a sound recording of the mark ought to be registered, as compared to the standard laid down by the EU wherein one has to represent such sound graphically.. To conclude, it would be relevant to note that in terms of purpose, both traditional and non-traditional marks are fundamentally the same and serve the same purpose.[38] It is the registration requirements which draw a line in the sand.

Author: Sanchit Sharma, 5th Year, BBA LL.B (Hons.) Himachal Pradesh National Law University, Shimla, in case of any queries please contact/write back to us at support@ipandlegalfilings.com or IP & Legal Filing

[1] Dr. Komal, Protection of non-traditional Trademarks: Issues and the Road Ahead, 11(2) TUCOMAT 695, 697 (2020).

[2] See, The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame v. Gentile Productions, 134 F.3d 749 (1998) (Court of Appeal (First Circuit)) (The claimant unsuccessfully argued that the design for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum in Cleveland, Ohio – effectively the building itself – was a trade mark) as cited in Gangjee, Dev, Non-traditional Trade Marks in India, 22.1 NLSI Rev 67, 80 (2010) .

[3] A Draft of Manual of Trademark Practice & Procedure, 3.2.4.

[4] rademark Act, 1999, §9(2), No. 47, Acts of Parliament, 1949 (India).

[5] Trademark Act, 1999, §2, No. 47, Acts of Parliament, 1949 (India).

[6] Laxmikant V. Patel v Chetanbhat Shah & Anr., A.I.R. 2002 S.C. 275 (India); ITC Limited v. Philip Morris Products SA, 2010 (42) PTC 572 (Del); Ramdev Food Products Pvt. Ltd. vs. Arvindbhai Rambhai Patel, AIR 2006 SC 3304.

[7] (The assertion is put forth on the understanding that when we talk about the registration of non-traditional marks, academic literature shows that such a mark, much like its traditional contemporaries, could be registered when all the aforesaid requirements are fulfilled. Furthermore, this conclusion is reached notwithstanding the arbitrary and universal criteria for the registration of such marks on the anvil of a test laid down for traditional marks.) See Vatsala Sahay, Conventionalising non-traditional Trademarks of Sounds and Scents: A Cross-Jurisdictional Study, 6 NALSAR Stud L Rev 128, 128 (2011); Majumdar, Arka, Subhojit Sadhu & Sunandan Majumdar, The Requirement of Graphical Representability for non-traditional Trade Marks, 11(5) JIPR 313, 313 (2006); Kuruvila M. Jacob & Nidhi Kulkarni, Non-traditional Trademarks: Has India Secured an Equal Footing, 9 Indian J Intell Prop L 47, 49 (2018); Dr. Mwirigi K. Charles & T. Sowmya Krishnan, Registrability of non-traditional trademarks: A critical analysis, 6 IJRAR 914, 916 (2019). Jacob, Kuruvila M., & Nidhi Kulkarni, Non-traditional Trade Marks: Has India Secured an Equal Footing?, 9 Indian Journal of Intellectual Property Law, 47 (2018), As cited in Mohit Joshi, Smell Marks: A New Era, 3(3) ILJMH (2020). https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2022/09/16/a-perspective-on-non-traditional -trademarks-and-the-difficulties-in-extending-ip-protection-to-them/#fn5; https://www.ijlmh.com/wp-content/uploads/Smell-Mark-A-New-Era.pdf at page 607.

[8] West Bengal State Warehousing Corporation v. M/S. Indrapuri Studio Pvt. Ltd. & Anr., (2010) 14 SCC 285.

[9] The words “combination thereof” referring to the preceding items, makes the definition of mark very comprehensive. Ashwani Kumar Bansal, Law of TRADEMARKS in India with Introduction to Intellectual Property 61 (Thomson Reuters 2014); Aishwarya Vatsa, Subject Matter and Pre-Requisites for Protection of non-traditional Trademark, 8 Christ U LJ 61, 75 (2019); Sanya Kapoor & Riya Gupta, The Five Senses and Non Traditional Trademarks 8 Supremo Amicus 214, 229 (2018). See also: Kuruvila M. Jacob & Nidhi Kulkarni, Non-traditional Trademarks: Has India Secured an Equal Footing, 9 Indian J Intell Prop L 47, 49 (2018); Gangjee Dev, Non-Traditional Trade Marks in India, 22.1 NLSI Rev 67, 73 (2010); Harsh Pati Tripathi, Potentiality of ‘Smell’ as a Trademark and its limitations, IP Law India (July 31st, 9:11 pm) https://iprlawindia.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Potentiality-of-%E2%80%98Smell-as-a-Trademark-and-its-limitations-harsha-tripathi.pdf.

[10] EUTMIR, Arts 3(3), 3(4). As cited in Intellectual Property Law, Bently, Sherman, Gangjee, & Johnson at page 957.

[11] Ralf Sieckmann v. Deutsches Patent-und Markenamt, Case C-273/00 [2002] ECR I-11737, [43]-[44] (Sieckmann); Shield Mark BV v. Joot Kist, Case C-283/01, [2003] ECR-I-14313.

[12] Dyson v. Registrar of Trade Marks (C-321/03) EU:C:2007:51.

[13] Philips Electronics BV v. Remington Consumer Products, [1998] RPC 283 as cited in PAUL TORREMANS,

HOLYOAK & TORREMANS INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW 426 (Oxford, 2019); Gangjee Dev, Non-Traditional Trade Marks in India, 22.1 NLSI Rev 67, 68 (2010) ; Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159, 162 (1995). (“human beings might use as a “symbol” or “device” almost anything at all that is capable of carrying meaning, [the statutory definition] read literally, is not restrictive.”)

[14] Ibid., Ganjee at 82

[15] Dyson v. Registrar of Trade Marks (C-321/03) EU:C:2007:51.

[16] American Foundation for Blind, What is Braille (July 28, 9:11 pm) https://www.afb.org/blindness-and-low-vision/braille/what-braille.

[17] Granted, of course, it counters an objection under §9(1)(a).

[18] G. Dinwoodie, Reconceptualising the Inherent Distinctiveness of Product Design Trade Dress, 75(2) NCL Rev 471, 561 (1997) as cited BENTLY, SHERMAN, GANGJEE, & JOHNSON, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW 957 (Oxford, 2022); David Vaver, Untraditional And WeltKnown Trademarks, 1 SING. J. LEGAL STUD. 7 (2005) as cited in Vatsala Sahay, Conventionalising non-traditional Trademarks of Sounds and Scents: A Cross-Jurisdictional Study, 6 NALSAR Stud L Rev 128, 137 (2011) (An argument to this effect could also be found when we see that motion and sound marks can gather the attention of Internet users considerably and more effectively than traditional marks. Therefore, there is, certain acceptable intelligible differentia in the use of a particular mark for a particular segment of the society.) See non-traditional Trademarks:The Spectrum of Distinctiveness in the Era of Globalization 1119). See also: Aishwarya Vatsa,Subject Matter and Pre-Requisites for Protection of non-traditional Trademark, 8 Christ U LJ 61, 65 (2019).

[19] Ashwani Kumar Bansal, Law of TRADEMARKS in India with Introduction to Intellectual Property 144 (Thomson Reuters 2014); David Keeling, David Llewelyn, James Mellor, Kerly’s Law of Trademarks and Tradenames 41 (Sweet & Maxwell 2017)

[20] §9(1) proviso.

[21] Geoffrey Hobbs, Q.C. in AD 2000 TM Case, (1997) RPC 168 at 175 as cited in Ashwani Kumar Bansal, Law of TRADEMARKS in India with Introduction to Intellectual Property at page 146.

[22] American Foundation for Blind, What is Braille (July 28, 9:11 pm) https://www.afb.org/blindness-and-low-vision/braille/what-braille.

[23] Consolidated Foods Corporation v. Brandon And Company Private Ltd., AIR 1965 Bom 35 (India).

[24] Id. at 27.

[25]Ashwani Kumar Bansal, Law of TRADEMARKS in India with Introduction to Intellectual Property 54 (Thomson Reuters 2014).

[26] Consolidated Food Corporation vs. Brandon & Co., AIR 1965 Bom 35 para 27.

[27] , The Trademark Rules, 2017, Rule 2(2)(k).

[28] JAMES MELLOR, KERLY’S LAW OF TRADEMARKS AND TRADENAMES 23 (Sweat & Maxwell, 2011). See also: Ashwani Kumar Bansal, Law of TRADEMARKS in India with Introduction to Intellectual Property 61 (Thomson Reuters 2014) ; Aishwarya Vatsa, Subject Matter and Pre-Requisites for Protection of non-traditional Trademark, 8 Christ U LJ 61, 75 (2019).

[29] BENTLY, SHERMAN, GANGJEE, & JOHNSON, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW 934 (Oxford, 2022) ;M. Handler & R. Burrell, Making Sense of Trade Mark Law, 4 IPQ 388 (2003)

[30] Vatsala Sahay, Conventionalising non-traditional Trademarks of Sounds and Scents: A Cross-Jurisdictional Study, 6 NALSAR Stud L Rev 128, 129 (2011).

[31] Trademark Act, 1999, §11, No. 47, Acts of Parliament, 1949 (India). (Relative Ground of Refusal)

[32] Trademark Act, 1999, §9, No. 47, Acts of Parliament, 1949 (India). (Absolute Ground of Refusal) (One might also note here that § 9 is an extension of the analysis we expounded upon earlier. The legislative intent is to only allow a mark which can graphically represent itself and has the capacity to distinguish itself with other marks.)

[33] Neoperl v EUIPO (Représentation d´un insert sanitaire cylindrique) ECLI:EU:T:2022:780.

[34] Haptic Trade Mark Application (Case I ZB 73/05) [2008] E.T.M.R. 16.

[35] Marcel Pemsel, The difficulty of protecting tactile marks, The IPKat (July 21, 9:11 pm)

https://ipkitten.blogspot.com/2022/12/the-difficulty-of-protecting-tactile.html.

[36] Id.

[37] See: United States Patents and Trademarks Office, Trademark sound mark examples, (July 22nd, 9:11 pm) https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/soundmarks/trademark-sound-mark-examples.

[38] Vatsala Sahay, Conventionalising non-traditional Trademarks of Sounds and Scents: A Cross-Jurisdictional Study, 6 NALSAR Stud L Rev 128, 141 (2011); Sanya Kapoor & Riya Gupta, The Five Senses and Non Traditional Trademarks, 8 Supremo Amicus 214, 230 (2018).